The Royal Navy built air stations and kite balloon stations to provide the Grand Fleet with aerial intelligence.

From the beginning of the war Admiral Sir John Jellicoe saw the potential of using aeroplanes to act as scouts ahead of the Fleet. They could be used to report back the position of enemy ships and submarines, but were not initially considered as an attacking force in their own right.

On 5th August 1914 three seaplanes and two aeroplanes were delivered to a field at Nether Scapa on the shores of Scapa Bay. Buildings were quickly erected, but were destroyed in early November by a gale. The air station was rebuilt, but was found to be of little use as too much of the shore was uncovered at low tide, making it difficult to launch seaplanes.

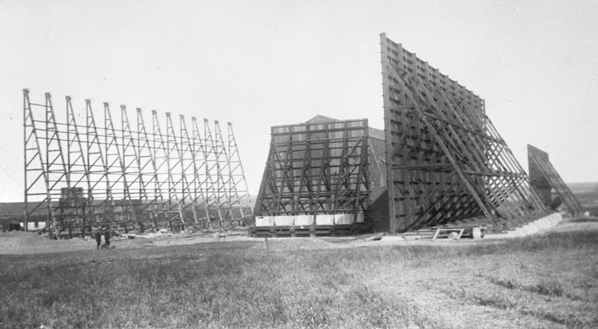

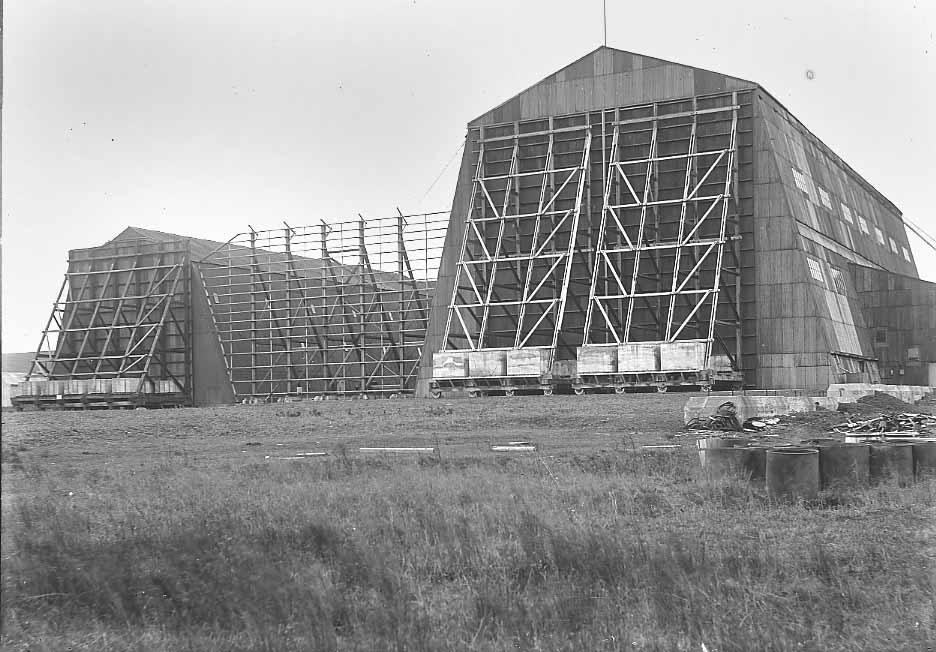

A new seaplane station was built at Houton in Orphir, with hangars, repair workshops, stores, a power station and accommodation huts. Another air station was built on the shores of the Stenness Loch, but the water of the loch was too shallow in places for a seaplane to land safely and it was also prone to cross-winds. It was later abandoned.Another air station was built at Swanbister in Orphir, but not completed until after the end of the war.

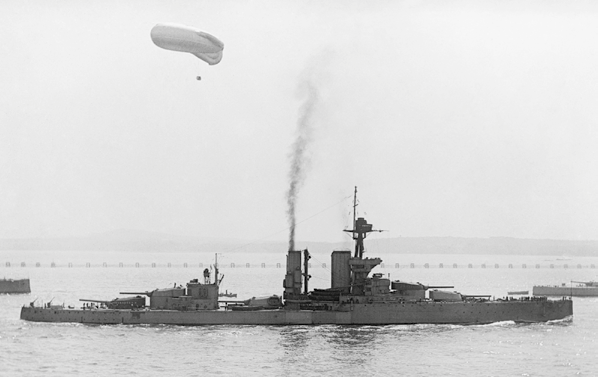

Kite balloons were used by the Grand Fleet as lookouts. They were tethered to battleships or merchant ships and provided an early warning of any mines or U-boat activity. An observer in a wicker basket hanging under the balloon kept in touch with the ship by a telephone link. Such balloons were of limited use in Orkney due to the

strong winds.

The balloons were inflated at Caldale and were transported to Kirkwall Bay or Scapa Flow tied to the back of a lorry. Caldale was also home for some

small reconnaissance airships, known as ‘blimps’. Again, they were of limited use due to the wind.

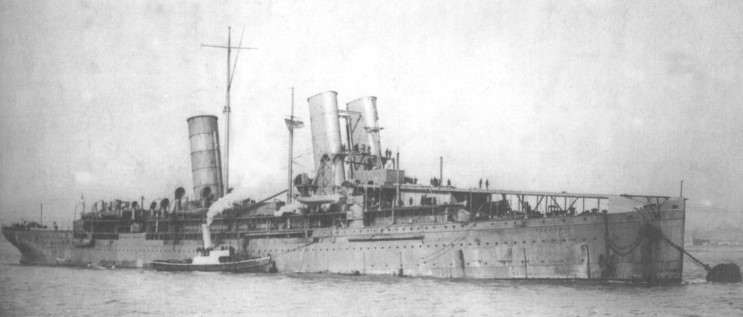

At this time seaplanes were launched from ships and had to land on the sea near the ship to be recovered. The former Cunard liner Campania was commissioned in 1915 as an aircraft carrier. Aeroplanes could take off from her flight deck, but had to land on shore. She was stationed in Pierowall, Westray, for a short time in July 1915 to provide a watch for submarines passing between Orkney and Fair Isle.

In 1917 Commander Edwin Dunning became the first man to land an aeroplane on a moving ship.

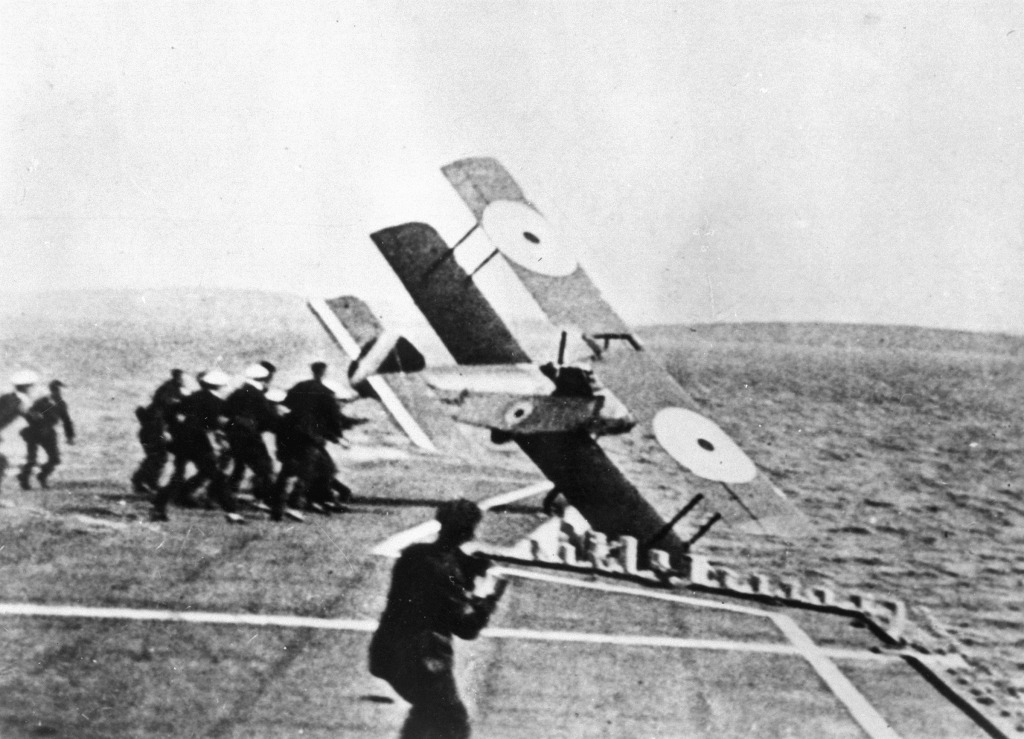

Twenty-five year old South African pilot, Commander Edwin Dunning, had calculated that if an aircraft carrier sailed into the wind this would reduce the speed of an approaching aeroplane, making it possible to land on the ship. With no arrester wires, the aeroplane would need grappling ropes fitted to the wing struts to allow the ground crew to catch and stop the aeroplane. The pilot would also have to fly past the ship’s funnels before landing on the flying-off deck.

Commander Dunning took off in his Sopwith Pup from Smoogro, Orphir, on 2nd August 1917 and flew towards HMS Furious. He skilfully manoeuvred his aeroplane past the ship’s funnels and landed safely on the flying-off deck, making aviation history. Sadly his triumph was short lived as he was killed just five days later, 7th August, attempting another landing on HMS Furious. An aviation committee later decided on flush-decked carriers, which opened a new chapter of naval history.

Scapa Flow’s anti-submarine defences were tested on 28th October 1918 when the UB-116 attempted to penetrate the naval stronghold.

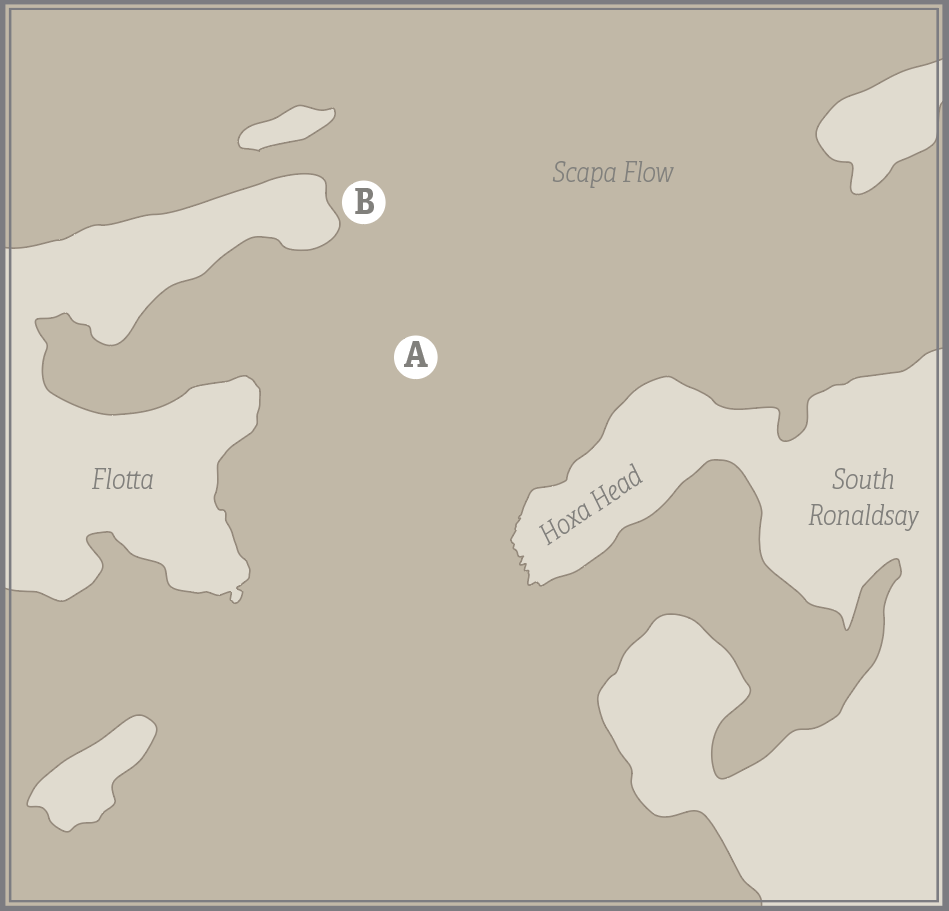

In both World Wars Scapa Flow’s boom defences were backed up by indicator loops on the seabed that could detect a large metal object passing over them and by hydrophones to listen for the sound of engines. If an enemy U-boat was detected a minefield could be detonated from the shore. This was the fate of the UB-116, which tried to breach the defences on the 28th October 1918 in a last desperate attempt to sink British warships. It was commanded by Kapitänleutnant Hans Joachim Emsmann, who was assured that there would be no mines in Hoxa Sound – in reality it was a suicide mission. Scapa Flow’s anti-submarine defences were tested on 28th October 1918 when the UB-116 attempted to penetrate the naval stronghold.

Its destruction was reported in The Orcadian on 12th December 1918:

“The enemy craft was detected near the entrance, howeve – possibly her presence was first divulged with the aid of the wonderful hydrophone – and when the vessel came over a minefield controlled electronically from a shore station mines were exploded. Other measures were immediately taken to make doubly sure the entire destruction of the U-boat. A number of

bodies were subsequently recovered, and a portion of the conning tower, which was salved and taken to St. Margaret’s Hope, was an object of intense interest to the islanders.”

Scapa Flow Museum is currently closed for a major refurbishment project, funded by Orkney Islands Council, National Lottery Heritage Fund, Historic Environment Scotland, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Museums Galleries Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Orkney LEADER fund. The project includes carrying out essential repairs to Pumphouse No. 1 and building an extension to house a new gallery, visitor facilities and café.

Visitors can virtually explore the buildings and former exhibitions at www.hoydrone.com/museum, a 3600 photo record of the main site museum site.

The Island of Hoy Development Trust website www.hoyorkney.com has a large Wartime Heritage section focusing on the WW2 history of Hoy.